Authors

interview Authors:

In this new segment, writers talk about their work with other writers.

In this new segment, writers talk about their work with other writers.

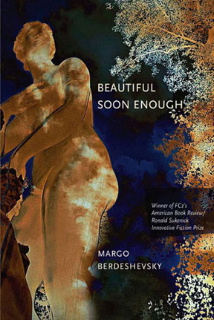

Rosalia Gitau talks with Margo Berdeshevsky, author

of the new book, Beautiful Soon Enough

RG: Margo Berdeshevsky was my first interviewee for

Paris Writers News, and I had no idea what to expect. I knew she was a writer,

poet, photographer, actress, humanitarian, world-traveler, and activist, but,

when I knocked on the door of her Marais apartment, I didn’t know what type of

person encompassed all of these activities- these lives.

What greeted me was an energetic blond, proudly

displaying streaks of grey, wearing turquoise earrings and thigh-high leather

boots over tight leather pants. She ushered me into the living room, cutting

through her office. It was a writer’s dream – large mahogany desk overlooking a

courtyard, an antique magnifying glass next to a well-used laptop. In the

living room, hung her photographs. Large, contemporary art pieces that betray a

collagist’s preoccupation with layering. Like her very full life, her written

and visual works display an urgency to fill it all in.

After our 3-hour conversation, I walked away awed

and inspired. Our interview, below, is just a handful of the topics Margo and I

covered: from her new book, a collection of short stories, entitled Beautiful

Soon Enough, to her politics, lovers, and life lessons. I admittedly broke the

first cardinal rule of interviewing: I fell in love with the subject.

RG: When did you move here?

RG: When did you move here?

MB: Just a year ago…it’s a completely different vibe, and I’m just

getting used to feeling like a grown-up.

RG: I was going to say, this is a very grown-up

apartment.

MB: What I loved about this is all of this is my artwork. The book [Beautiful Soon Enough] is illustrated

with many of my images. I wanted all of the images in the book; I don’t like

the Parisian gallery scene very much [though]. I had a show at one point, a

series of Cuban photographs. I got to see the gallery scene and it’s

pretentious. It’s one way to sell art but I thought if I can find a space [my

apartment] where I can make a mini-gallery and invite clients two or three at a

time, that’s going to work better than playing that other game.

RG: Where do you feel at home?

MB: I’m one more of the alienated humans who live in Paris- this is more home than not. But I lived

for many years in the Hawaiian islands where place and home and ancestry and all that sort of thing are

paramount and profoundly important and, because my dearest friends partook in

the belief system, I learned it very well. But, in fact, plunk me down anywhere

and I’m going to make a life. So, I really understand that the [conventional]

version of being a human doesn’t track for me. I’m not a mommy, I’ve been

married lots of times, but I’m not married now, so the paradigm that works for

lots of people had never worked for me. That’s what made me an actress first-

living other people’s lives- and it certainly is what made me a writer.

RG: So, what is your creative process?

MB: A lot of work has come out of my darkest nights because I’ve got to do

something with them and eventually I find that they form some little nugget of

my understanding. I’ve moved through numerous art forms and continue to [do so]

. I’m a collagist at heart in the same way that my images are layers and layers

of imagery. The writing is similar; I have a poetic voice that has been written

about in reviews and spoken about and I use that element in whatever I write.

So the poetry is always there on some level, the imagistic mind is always there

on some level.

RG: So, do you begin with the words or do you begin

with the picture? Do you borrow from you own life? Those of others?

MB: I steal from everything. There is only one book that I’m worried about

and that hasn’t come out yet.

MB: I steal from everything. There is only one book that I’m worried about

and that hasn’t come out yet.

I borrow from

my life. I borrow from everything that I experience. I remember seeing this

sign in a window once, I think it was a quote of Picasso that said I steal from the sun but I only steal from

the best that may be a misquote, but I like it. When people ask if the

stories are based on my own life, I can only say: ‘yes, no, and none of your

business’. Of course I use some of what I’ve lived and then I have permission

to lie. And I’m a good liar. [Beautiful

Soon Enough] is doing quite well. What I’m finding is, that people of all

ages are relating to an element of nakedness and the truth about being the

woman.

RG: What do you mean, ‘being a woman’? Has living

in Paris helped your understanding of ‘womanness’?

MB: [There is a] part of me that

is deeply interested in what it is to be a woman… deeply interested in what it

is to be a sexual being.

I think Paris- of the many places that I lived- is

the best place to be a woman. In the sense that a woman is recognized for being

a woman at all ages: a very young woman, a middle-aged woman, une femme d’un certain age. I can walk

in the street, make eye-contact with a man, know that there is a spark and then

move on with my day, he moves on with his day and we didn’t have to go to bed.

It’s just an acknowledgement of the life force, and for that I love it. My

ongoing fantasy- and it has happened- is that I meet a stranger on a street and

we go for a drink and its a lovely time.

RG: And the ‘womanness’ aspect?

MB:I think it is to honor one’s vulnerability. It is to be willing to

open. I think what every woman has her own kind of beauty. I think an old

woman’s hands are just as beautiful as a teenager’s. But I think it is to

respect the beauty in oneself; these things are true for men as well, but I

know them from inside my own body. We did a reading at the Village Voice [and]

some man in the audience- a very Cartesian Frenchman- had noticed that the stories

were, in a large degree, attempts to find an experienced freedom- a woman’s

freedom.

An intense experience I think many people are afraid of and I think that’s why

the book is touching certain cords because in each one of the stories, the

characters are acknowledging their desire for an intense experience and

pursuing it with all the risk that that takes and all the pain that that may

bring with it and all the curiosity that is inherent in that.

RG: But what if the intense experience

comes with collateral damage? There could be a spouse, or children involved-

should one pursue such a dalliance or not?

RG: But what if the intense experience

comes with collateral damage? There could be a spouse, or children involved-

should one pursue such a dalliance or not?

MB:There is a story in [Beautiful

Soon Enough] about the 5 a 7

lover. If you had asked me the question a dozen years ago, where my own

yearnings had a very proscribed ‘This is

the way it is, this is the knight on the white horse I wait for, this is the

fantasy and it will be no other way’ then I would answer quite differently

as I would today.

RG: You don’t strike me as a woman with a list of

requirements for a partner.

MB:Well, I’ve certainly had them and I’ve been married legally or

illegally three times so I’ve tried the paradigms I wanted for my heart over

and over again and had to grow up out of my fantasies into some of my reality.

And so my reality is still questing, my reality is still unsatisfied, and my

reality is still what’s waiting next on a bridge. But I’ve learned to respect

that each person is entitled to his/her jardin

secret.

Relationship

[are] founded on humility and trust [but] trust is an interesting word to me

because if I say “I trust you’, you have a right to say ‘trust me with and for what?”. Is it only that

you own my sexual organs? Or is it that you trust me to be kind and respectful of your feelings? Respectful of

your feelings may or may not mean I tell you what I did between 5 a 7. It is possible that those hours

are my jardin secret and they give me

the strength or the courage to face life in all the other ways.

But I don’t

have a moral fixation at this time in my life that says ‘no way Jose’. I have

women friends who are shocked by that.

RG: What made you change your views?

MB:I began to experience that my fantasies of how it should be didn’t

bring me any more joy than the realities of those times when I lived an intense

experience, it was for a proscribed period of time and I had to let it go.

That’s a lot of hard work on the soul level- letting go. But if you’ve had to

let go a few times in your life then you also learn to treasure what you have

when you have it.

RG: Is this what you meant before when you said the

paradigm of love and life doesn’t apply to you?

MB:I think nearly every woman I know was given the paradigm: ‘you will be

loved well and forever’. I think the all-or-nothing paradigm is what women

especially are given to hope for.

RG: I think that is very much still the case for

young women today.

MB:What I have been finding is that when I did the reading for this book

at Shakespeare & Company- the youth of the audience that is showing up to

the readings, I was told, had a level of attentiveness, saying, ‘I haven’t

experienced that yet. But I’m really listening. I’m really listening to what

engagement with another human being is, at least this wish for engagement’.

RG: Can you imagine a man writing something similar

to this book?

MB: No, I don’t think so. And the

men who have read it have told me that they are learning things about being a

woman that they didn’t think were essential to a woman. And because the stories

go from very young women to much older women, it’s across the board. From

getting down without being raunchy- I think there is that in all of us.

RG: What are you optimistic about and what are you

pessimistic about regarding what is happening in the world today?

MB: I’m optimistic that we can speak to one another. I’m optimistic that I

can find one person at a time with whom I can open the heart and open the lines

of communication. In the years when I lived in the Hawaiian islands, I was trained, in traditional healing.

I ended up going to Sumatra after the tsunami and doing some hands-on work with

the survivors there. I’m optimistic that there is some understanding that we

can be helpful to one another.

I’m profoundly

pessimistic that we’re so in our little boule

that we’re not willing to always do that: that’s what the whole healthcare

debacle is about. I’m living here in Paris but that doesn’t mean that I’m not

paying attention to what’s happening in the country where I hold a passport.

We’re warriors, we’re greedy, we’re disrespectful of one another’s differences.

I can add my little drop to the ocean. I can try and add something that makes

it better, but we’re not there. I’m not there. That level of consciousness is

oddly more dealt with in my poetry than in my stories. My poetry book But a passage in the Wilderness deals very

much with my sense of all we’ve encountered with humanity in our time.

RG: Does our apathy sadden or anger you?

MB: I’m a witness. I’m able to mourn for it, through my words. I’m able to

speak to it. Best Love And Goodbye (from But a Passage in Wilderness) was written

at the very beginning of America’s entry into the Iraq war. I’m by no means a

supporter of what [America’s] been doing. I’m allowed to be critical about it

and I’ve used my words to say so and sometimes, they hit home for people.

I marched in

the very first gathering of Americans living here in Paris. We walked down the boulevard saying we

are Americans saying no to America’s entry into the Iraq war. I looked at the

people lined along the streets and what flashed for me were the pictures of the

French who had lined the streets thanking the Americans for the Liberation

(following WWII). I heard those

descendants- you know the children and grandchildren- saying thank you to those

Americans who joined that particular march; they [the French on the street]

were saying thank you to those Americans who they could look at in the eye

[thanking us] for not joining the herd. The Bush years were definitely herd

years. And we have a little bit more hope now, but not enough.

You asked me

before what I’m pessimistic about what I’m optimistic about? Because I stand

between several generations at this time, I’m both. I’m optimistic about my

opportunities and I’m realistic about what has happened and what has not

happened. I make myself no promises, really. And I don’t know whether the life

that I’ve created so far will widen as much as I hope, or will continue to

widen as much as I hope.

RG: But you’re hopeful about it?

MB:I am, I am. I have reason to be hopeful. Some good things have

happened the last couple of years. I spent years praying for these books to

come out and when they started coming out, and people started reading them,

that was a good thing, it continues to be a good thing. The friendships that

I’ve made over the years are profound ones.

Is the

community I participate in as wide as it could be? Not always, not always. I’ve

my own cross to bear and this is also the atmosphere out of which the work has

grown. Maybe for now, the words optimist and pessimist don’t apply in the same

way they have at other times in my life.

RG: So community is important as a writer?

MB: I had been with a man for quite a long time, who had children who

separated from their mother- the children were fairly grown. We had been in a

relationship for four years at that time maybe, a little bit longer, and [one

day] we go out to breakfast with a very dear friend of mine, who had five

children at that time. We’re talking about all manner of things and she says

something and I say something along the lines of what it is to have children

and what is it to not have children. He turns to me and he says: ‘Well, of

course, she [my friend] is so much

more of a woman that you are, you’re not really a woman because you haven’t had

a child’. My friend stood up from the other side of the table and slapped him.

To this day, I

bless her and I thank her for that because it opened my eyes to everything that

was going wrong in that relationship. Hopefully, I’ll have friends that will be

those humans in my life. But no, I’ve never needed to duplicate myself as so

many on this planet need to do. Do I duplicate myself in the writing? In some

ways. Only I do it in many different faces, hearts, and psychologies, I think.

RG: What tips can you offer others who want to be poets or writers? What are

some pitfalls that you would suggest avoiding for a young aspiring poet/writer?

MB: If you want to write then write. I have serious qualms about the whole

burgeoning MFA industry in the US for many reasons. One, the homogeneity of the

work that comes out of it, but also the illusion it gives to young writers that

all they have to do is spend their $30,000 bucks- which already puts them into a lifetime of

debt- and for that they believe that they deserve their first book to come out

instantly, long before they have the life experience or the literary experience

to really write a book. A book takes years and years and years. I was terribly

impatient, as we all are: ‘I wanna be discovered! I wanna be the shiniest blue

pebble on the beach! Find me! Love me!’. But it takes a hell of a long time and

when I look at the work of mine that has been published, I’m so happy that it

wasn’t published earlier- it wouldn’t have been good enough. But I didn’t know

that then. I was waving my hand in the air going ‘ me, me, me!’

The classic

piece of advice is read a lot. And that’s good advice. I find that for myself

when I’m deeply writing, I almost stop reading, I can’t take in anymore. I’d

say read in many different genres- you can’t be a poet and only read poetry.

You need to have read history, to have read the big fat novels, you need to

have read the cereal box. But when I’m deeply writing, I go writing.

My

understanding comes from every minute I’ve been alive so far and still is

coming. When I go dry, when I go empty,

when I can’t write anymore, often it is that I really emptied out the well.

I’ve used all I think I know so far and I think to [myself], I’ve got to live

some more!

RG: Did you ever take poetry classes?

MB: No. I attended a couple of workshops, but I’m not very comfortable in

workshop atmospheres for the most part, I’m a bit of a hermit. I write alone

and I have three friends that I can send

a raw manuscript to and say ‘take a look at this’.

RG: Do you feel your writing is too personal to

share widely in the beginning stages?

MB: It’s just a different way of working. I’m not easily influenced by a

teacher, any more than spiritually I would be influenced by a guru. I’m

hard-headed. I’m curious and I dig my way through my troubles.

It’s a terribly

fine line- how to access, as an artist, the truths we hold within ourselves.

Whether we tell it exactly how it is or whether we lie about it afterwards,

whatever we do to make it accessible to ourselves and accessible to an audience

- and hope to put it back into safe-keeping and go have a glass a wine or go

make love.

I remember as

an actress I was literally naked. I had to come on stage strip naked and get

into bed with the other actor.’ I used to tell myself before I went on-stage

that they were all stark naked.

RG: Does that really work?

MB: I turned a switch in myself, to remind myself that under your sweater

you’re just as naked as I am. Under your defenses, you’re just as naked as I

am.

RG: Why do you write? Do you write because you need

to or because you want to?

MB: It’s both. I love words. They’re my tools to go deep. They’re my

shovels to dig down with.

RG: So, what’s next?

MB: I leave in 10 days for New York City. [My old Performing Arts teacher] is

now 96 years old and still dances the tango. She read my new book and

said: ‘I stayed up all night reading it.

It’s the sexiest thing I’ve ever read, why don’t you come and do a salon in my living-room in New York?’. And so, she is inviting twenty-five

of her nearest and dearest. In a way that’s more of a high, more of the sense

of succeeding with the book than anything I can imagine. I am [then] going to

the AWP conference in Denver. I get to meet the Fiction Collection crowd and

they are some amazing writers [attending]. Innovative fiction, I’m still

discovering for myself, but I think I belong to that tribe.

RG: To those future Literature courses that will be

dissecting your work - what is something that you do not want to be interpreted from this book?

MB: That’s a great question. It’s not purely autobiographical!

By all means

identify yourself as the reader because that’s a goodly part of why I’ve done

it. I’ve tried to touch those cords that are so human and so vulnerable in me

that you will find your own string vibrating; if that happens then it’s

successful. But if you stand back in a corner and think: ‘wow, I wonder what

made her think of that?’, then it’s not happening. But so far, what I’ve

discovered is that people are going: ‘how did you know about those elements in

my open life?’ and that pleases me a lot.

Literature is

to be experienced. It’s another of the hungers. Whether it’s for analysis- I

don’t think so. At least, that’s not ever how it served me.

To order Margo

Berdeshevsky's books from Amazon Author page: http://tinyurl.com/ygft9wu